Matthew Hofer

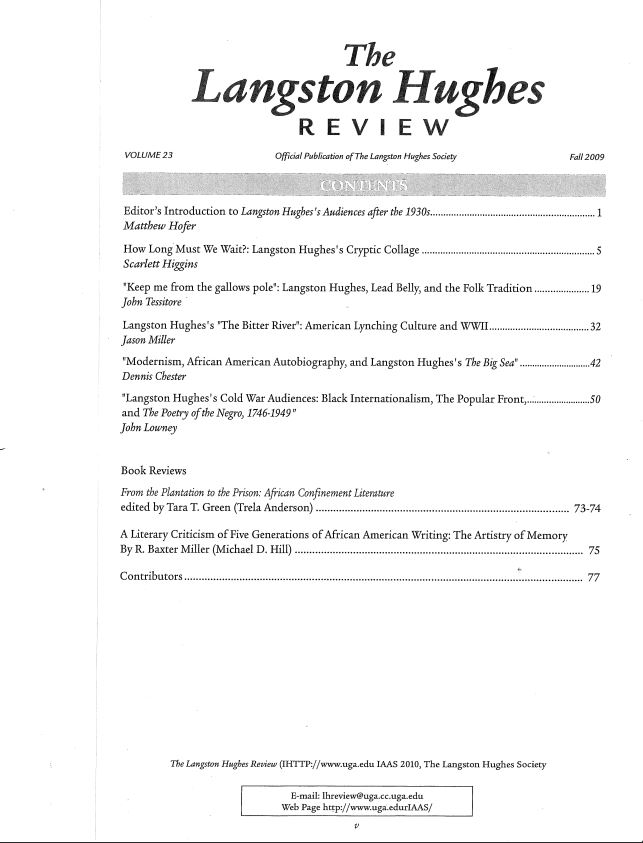

Matthew Hofer has edited or co-edited seven book-length projects: the language-centered trio LEGEND (2020), L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E newsletter (2020), and The Language Letters (2019); volumes on the politics and aesthetics of Ed Dorn (2013), Sinclair Lewis (2012), and Oscar Wilde (2009); and a special issue of The Langston Hughes Review, "Langston Hughes's Audiences after the 1930s" (2009).

His forthcoming monograph Omnicompetent Modernists: Poetry, Politics, and the Public Sphere will be published in spring 2022 in the University of Alabama Press series Modern and Contemporary Poetics. He is currently working on a book on postwar American poetry, correspondence, and thought, while seriously deliberating another on “sparseness” in twentieth-century writing.

His work to date has appeared in such periodicals as Modernism/Modernity, New German Critique, Contemporary Literature, Jacket2, American Literary Scholarship, The Journal of English Language and Literature, and Paideuma, and he has also contributed substantive chapters to many edited volumes, including The Cambridge History of American Poetry (“Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, and the East Coast Projectivists”), The Blackwell Companion to Modernist Poetry (“Contemporary Critical Trends”), and Ezra Pound in Context (“Education”).

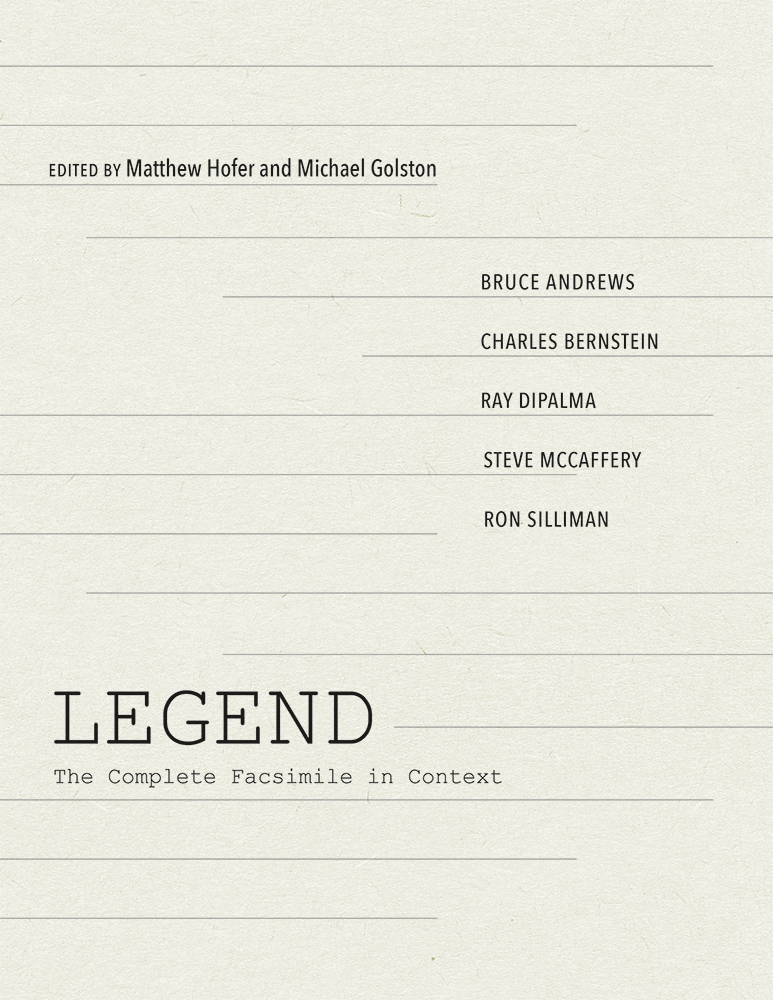

LEGEND: The Complete Facsimile in Context

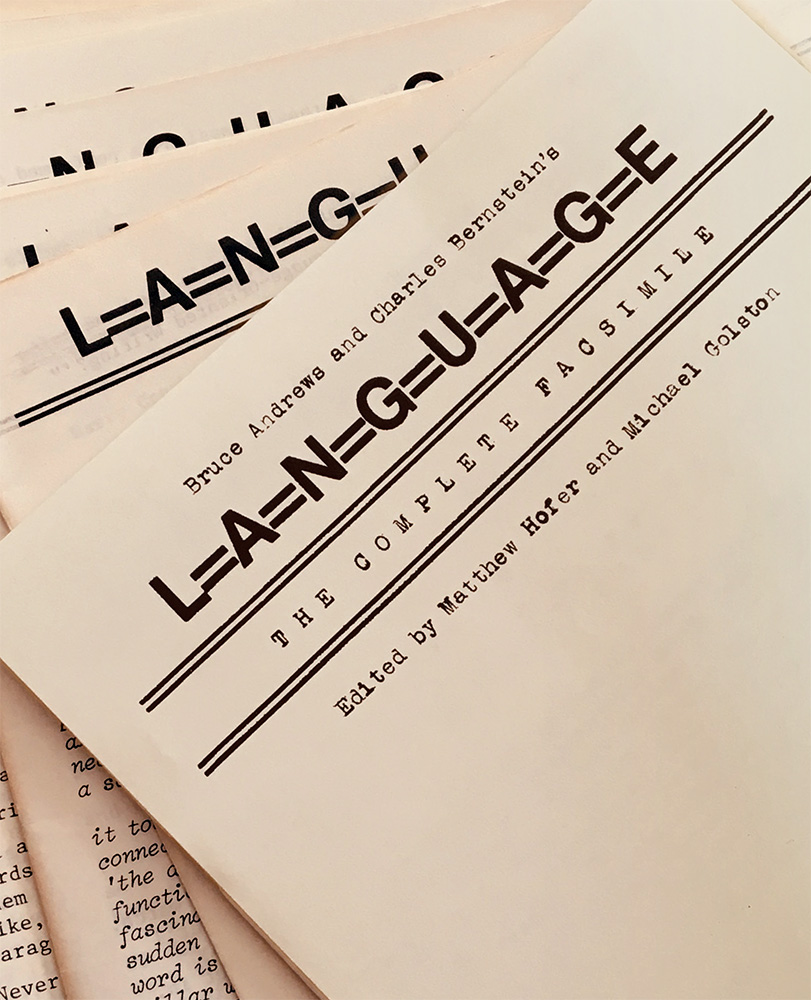

Bruce Andrews and Charles Bernstein's L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E: The Complete Facsimile

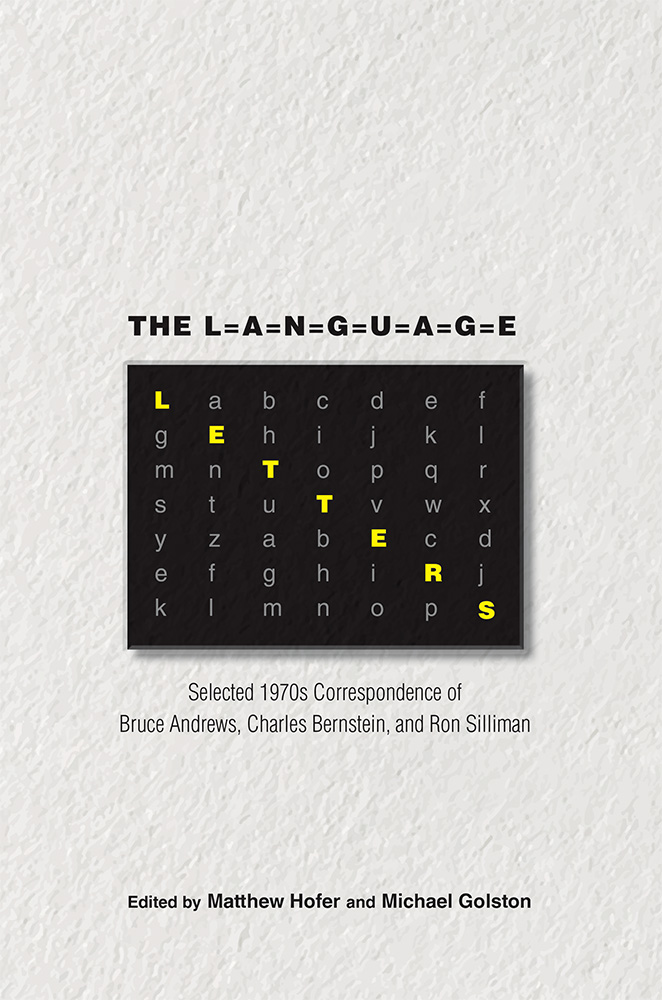

The Language Letters: Selected 1970s Correspondence of Bruce Andrews, Charles Bernstein, and Ron Silliman

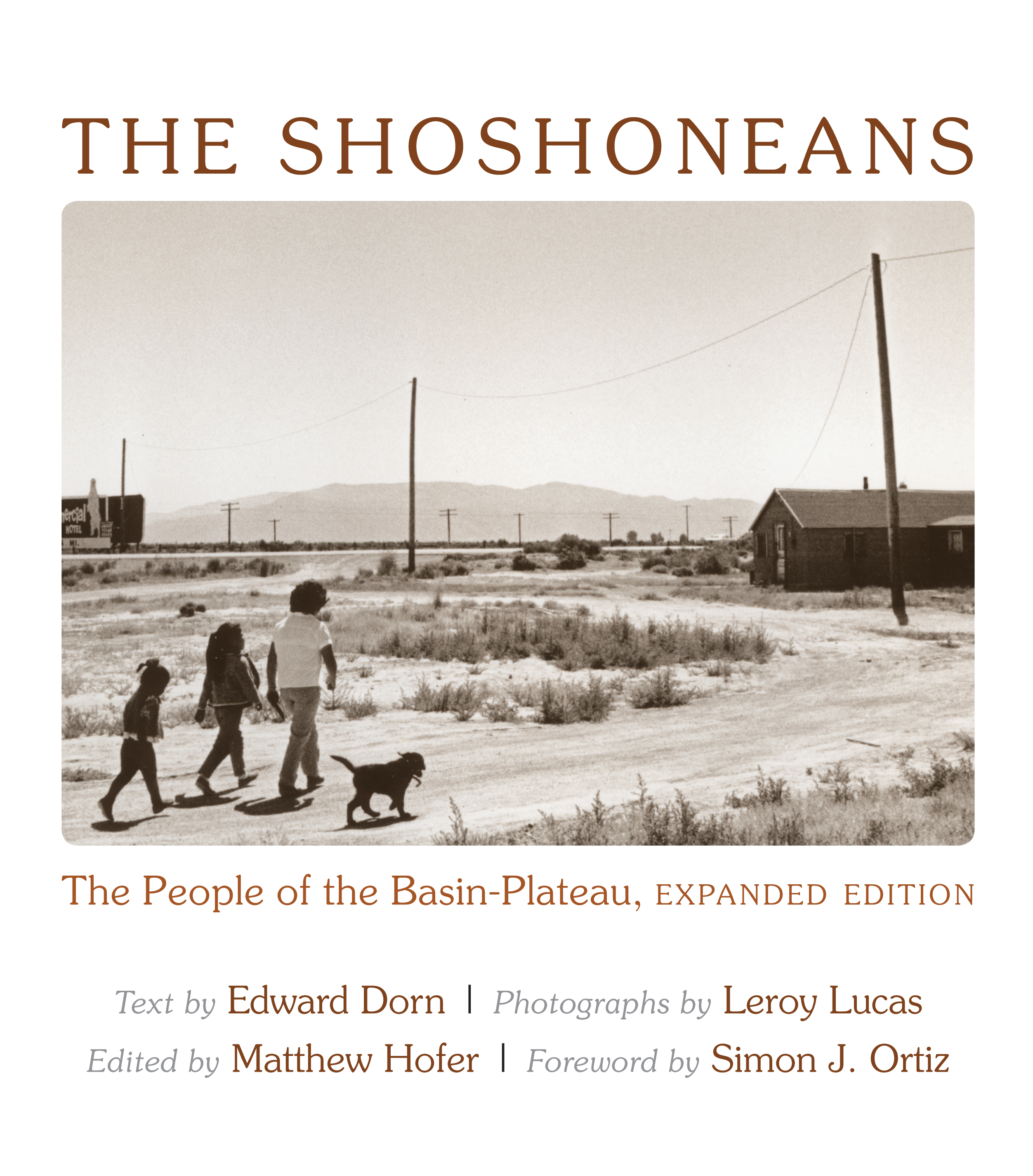

The Shoshoneans: The People of the Basin-Plateau

Sinclair Lewis Remembered

Oscar Wilde in America: The Interviews

The Langston Hughes Review

| Punctuation has value only as aid to interpretation. Where it produces confusion rather than clarity, it is of no value at all. The conventional punctuations of Hughes’s career lend themselves more to confusion than clarity. An easy division into three parts, characterized by a series of neat fits by decades—where a “folksy” 1920s is followed by a “radical” 1930s and then a “retrenched” 1940s—simply maintains a schematic sense of a complex writer, in which abstracted positions on ethnicity and class may be viewed as separate concerns rather than related ones. For a defender of the downtrodden and oppressed like Hughes, these concerns are fundamentally related, and from this perspective his radical work should be understood as an extension and amplification of his folk ethics rather than a break from it (style is, of course, another matter). The ideals that inspired him to advocate for interracial and intra-racial equality also underwrote his condemnation of global capital and informed his search for international models of political equality. Hughes was no more prone to recognize dissonance in these concerns than to accept accusations that his dissent from American orthodoxy compromised his patriotism. He always fought for versions of a single, coherent cause. The point is, if there was a meaningful shift in Hughes’s career, it is properly located not between the 1920s and 1930s, but after pressure from the government he had perhaps naïvely endeavored to serve had “dulled the reflex of his courage,” as Arnold Rampersad tactfully put it. Without taking its existence as a given, the essays collected in this special issue help gauge both the extent and the significance of that shift. The three questions their authors ask are, first, what audience(s) did Hughes seek after the 1930s, second, how did he attempt to reach them, and, third, what did he hope to accomplish in the process? —Matthew Hofer, from Editor’s Introduction |